New cities as economic engine

Projects

-

Do political connections help or hinder urban economic growth?

Evidence from 1,400 industrial parks in China

-

The birth of Edge Cities in China

The effects of new industrial parks on local production activity and consumer behavior in close proximity to the new parks.

-

The Revealed Preference of the Chinese Communist Party Leadership

Why do some Chinese leaders choose the “wrong” city to site expensive place-based investments (industrial parks)?

-

Publications

Our publications related to these projects

Industrial Parks: Productivity Gain and Misallocation Cost

Evaluation Place-based Industrial Policies in China

Do massive investments spent on industrial parks facilitate local economic development in China?

Since 1982, the Chinese Central Government has built thousands of industrial parks. Although these parks only occupy 0.1% of China’s total land area, they contain 40% of the nation’s manufacturing jobs, contribute 10% of China’s GDP, and 33% of foreign direct investment.

China’s government has spent hundreds of billions of dollars to invest in new industrial parks with the intent of boosting economic growth and generating spillovers for the local economy. Are these investments effectively spent?

Do political connections help or hinder urban economic growth?

Evidence from 1,400 industrial parks in China

Over a period of more than three decades, the Chinese government has created more than 1,400 new industrial parks, which have played a key role in creating manufacturing jobs and in attracting foreign direct investment, both nationally and locally. Provincial leaders who choose the location of such parks have political career incentives to select sites that increase regional economic growth, but also to select sites that reward city officials with whom they have connections. By exploiting plausibly exogenous changes in political connections, we document that city officials with connections to key provincial decision-makers are more likely to win parks. We estimate the heterogeneous urban growth effects of attracting such place-based investments. We find that industrial park sites chosen largely as a result of favorable political connections generate lower economic benefits than those chosen largely based on their economic fundamentals.

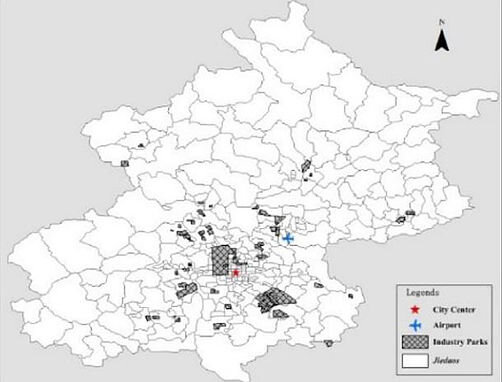

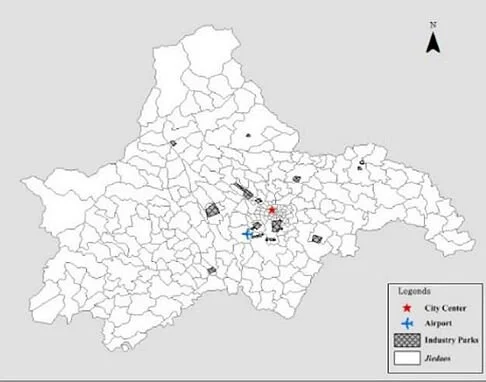

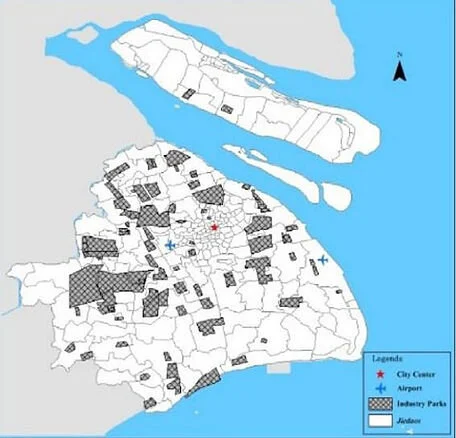

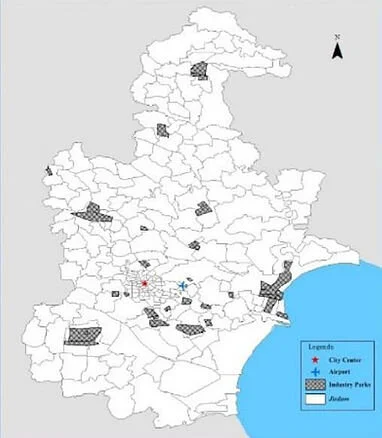

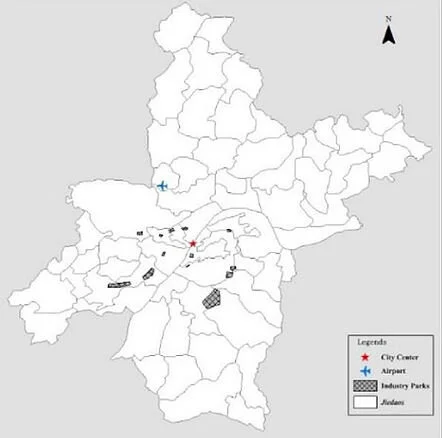

National- and Provincial-level Industrial Parks Built in China (by the end of our study period)

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that political favoritism plays a role in determining where investment resources go.

We empirically examine the impact of parks on subsequent urban economic growth. Our results show that when the initial location decision is mainly driven by politicaln connections, the creation of an industrial park generates lower levels of economic growth than is evidenced in cities that were selected in spite of a lack of political connections.

The birth of Edge Cities in China

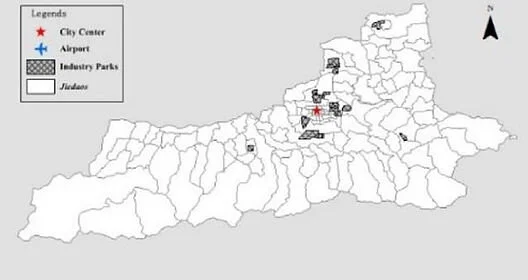

This paper tests for the effects of new industrial parks on local production activity and consumer behavior in close proximity to the new parks.

Using the opening of 110 industrial parks across 8 major Chinese cities (shown above), we quantify the spillover effects on productivity, wages, employment, homes sales, and retail activities for economic activity close to these new suburban centers of productivity (results shown below).

Note: Parks' impact area = within two kilometers of the parks' boundary

Using the opening of 110 industrial parks across 8 major Chinese cities (shown above), we quantify the spillover effects on productivity, wages, employment, homes sales, and retail activities for economic activity close to these new suburban centers of productivity (results shown below).

We find that 70% of new industrial parks built during 1998–2007 in the eight major Chinese cities generate positive total factor productivity (TFP) spillovers in their vicinity, while 30% of those parks turn out to have negative or insignificant TFP spillovers.

This kind of place-based policy can produce significant gains. The results speak to questions about the value of place-based industrial policy, while also providing valuable new data about economic spillover effects — the extent to which the presence of industries creates additional economic activity.

The Revealed Preference of the Chinese Communist Party Leadership

In the previous paper, we documented that 30% of parks failed to generate local agglomeration benefits. The fact that we observe very different returns raises a question about the initial site selection problem.

Why do some Chinese leaders choose the “wrong” city to site expensive place-based investments (industrial parks)?

This paper presents a revealed preference analysis of Chinese leaders’ priorities. We assume that each provincial leader has the same objective function defined over three attributes: economic growth (value added GDP), expected inequality reduction (within-province city-level Gini coefficient based on GDP/capita), and rewarding social connection (whether there are social connections between provincial leaders and city leaders).

In this project, we constructed three unique and comprehensive datasets.

Dataset of Industrial Parks

Our dataset of industrial parks covers 276 prefecture-level cities during the period of 1988-2008. During our study period, 1,417 national and provincial level industrial parks were built in these 276 cities.

2. Dataset of city attributes

3. Dataset of city attributes

A data innovation in this project is our creation of a detailed social networks database that allows us to track the long term connections between provincial leaders and city leaders at different points in time.

To build these social connections, we construct a dataset on the city and provincial leaders between 1980 and 2010 in China by undertaking a large-scale data collection from Duxiu, a local Scholar Search Engine with millions of digitized literatures, newspapers, journalists and books in Chinese provided by China’s CNKI. This data set enables us to construct four measures of connection based on information on workplace, birthplace, alumni networks, and political factions.

We reconstruct the choice set of possible locations to build a new park and we observe where the park is actually built.

The graph below demonstrates the results of our choice model:

Estimated GDP increase and Gini coefficient change attributed to a real or a hypothetical park in a city

We find that a provincial leader is willing to sacrifice 1.6% of the province’s annual GDP for helping a connected subordinate. Although Chinese Communist Party may be willing to bear some cost to achieve social stability by reducing income inequality, the misallocation cost triggered by rewarding social connections is a pure loss of social welfare.

Toward Urban Economic Vibrancy

Patterns and Practices in Asia's New Cities

JUNE 2020 Book Release

Editors: Siqi Zheng and Zhengzhen Tan

Asia has experienced a dramatic urbanization process over the past few decades. The rapid urbanization trend has reshaped Asian economies as cities generate agglomeration economies; enabling workers and firms to interact in close physical proximity; allowing specialization and nurturing entrepreneurship.

Urbanized Asia has become a global powerhouse, generating more than one third of the world’s total GDP. One significant urbanization trend across Asia is the widespread prevalence of “new planned cities, where public and private sector collaborate to generate growth engine for the economy.

What are the success factors driving new cities economic vibrancy?

What’s the role of digital urban system in enhancing urban vibrancy?

What’s the mechanism of public and private partnership in new city making?

What’s the important yet understudied relationship between market mechanism and non-market forces such as public policy and regulations?

Team

Siqi Zheng

MIT Sustainable Urbanization Lab, Department of Urban Studies and Planning,

Center for Real Estate

Weizeng Sun

Central University of Finance and Economics

Jianfeng Wu

School of Economics and China Center for Economic Studies (CCES), Fudan University

Matthew Kahn

Johns Hopkins University and NBER

Publications

Kahn, M. E., Sun, W., Wu, J., & Zheng, S. (2020). Do Political Connections Help or Hinder Urban Economic Growth? Evidence from 1,400 Industrial Parks in China. Journal of Urban Economics, 103289.

Kahn, M. E., Sun, W., Wu, J., & S. Zheng. (2018) The Revealed Preference of the Chinese Communist Party Leadership: Investing in Local Economic Development versus Rewarding Social Connections. No. w24457. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Zheng, S., Sun, W., Wu, J., & Kahn, M. E. (2017). The birth of edge cities in China: Measuring the effects of industrial parks policy. Journal of Urban Economics, 100, 80-103.